Many sights and sounds greet visitors to Ozarks Technical Community College’s Lincoln Hall. They might hear power saws humming in the construction lab, watch future nurses take blood pressure or listen to the whir of cleaning tools in the dental clinic. While that describes Lincoln Hall and its purpose today, the building has a rich history that goes back nearly a century.

“It was the only school for Black children here in Springfield, Missouri, but this was one of the best Black schools in the state of Missouri,” said Norma (Bland) Duncan, 81. She attended Lincoln School, as it was known then, from 1945 until integration allowed her and her classmates to attend Central High School in 1950s.

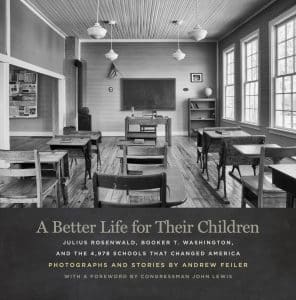

Opened in 1931, Lincoln School was one of 4,978 Rosenwald Schools built between 1912-1937 in the South and neighboring states to educate African-American children. Julius Rosenwald, then the leader of Sears, Roebuck and Company, established the fund that bears his name to construct the schools after meeting with famed African-American educator Booker T. Washington.

“These schools literally transformed America,” said Andrew Feiler, who is publishing a photo documentary book of Rosenwald Schools. “There was a large and persistent Black-White education gap in America before World War I. That gap closed precipitously between World War I and World War II, and studies have shown that the single biggest driver of that achievement were the Rosenwald Schools.”

Civil rights leader Medgar Evers, author Maya Angelou and Georgia Congressman John Lewis are among many well-known Americans who attended Rosenwald schools.

For Norma Duncan, Lincoln represented much more than just an education. The school was on par with church and family in importance because it was the community’s hub.

“They had all kinds of activities for kids. Every spring, the grade school kids would put on a play, and everyone would make costumes, and the kids would research their parts and memorize their lines,” Norma remembers with a smile. “And there was adult education at night for people who had not had the opportunity to go to school so they could learn to read and write.”

Norma recalls with pride some of the teachers who touched her life, like Mr. Brooks, who started the band and orchestra at Lincoln and was also a talented illustrator. She also reminisced about the industrial arts teacher, Mr. Hughes, a licensed pilot, a veteran and a mason. Norma fondly remembers her neighbor, Mrs. Bartley, who taught her in the third grade, and the art teacher Ms. Tolliver who made a papier-mâché figure of the boxer Joe Lewis for Black History Month.

Following the landmark Brown v. Board of Education Supreme Court case in 1954 that led to schools’ integration, African-American students were allowed to attend Springfield Public Schools. Lincoln remained open until 1955 for the seniors who wanted to finish their high school education at Lincoln. Later on, the building became an integrated junior high and, eventually, the Graff Area Vocational-Technical School before it became part of OTC and was renamed Lincoln Hall.

Lincoln was built in the later phase of the Rosenwald program, and that may be why it’s still standing and remains an admired piece of architecture.

“It was only in the later years of the Rosenwald program that they built two and three-story buildings out of concrete and masonry,” Feiler said. “Also, in the early years, the schools did not have any architectural ‘niceties,’ but in the later years, those restrictions were loosened, and that’s why Lincoln has some art deco features.

Of the nearly 5,000 Rosenwald Schools, only about 500 survived. Lincoln is in a small group of just five former Rosenwald Schools that are still used today for education. The building has been expanded, renovated and rehabilitated over the years, but Lincoln’s “bones,” both in structure and spirit, remain intact.

“It’s unbelievable how beautiful and big it is now,” Norma said with pride. “But the thing that I really love is that it was designed for education, and they kept it that way.”

Andrew Feiler’s book, “A Better Life for Their Children,” will be published in April. A touring exhibition of his photographs of the Rosenwald Schools will debut at the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta on April 1.